I’ve written many times about how we fell in love with Tasmania, but perhaps one thing I haven’t spoken enough about, is the Indigenous history of Australia’s island state.

There’s a reason for that; during our 3 months in Tasmania, although we learned a lot of history, I’m sad to say we didn’t learn much about Tasmania’s first peoples. There were snippets on a couple of signs, and a small amount I managed to track down at Port Arthur, but sadly I don’t feel there’s enough information in general tourist areas. There may be more accessible information on Flinders Island, Bruny Island or Maria Island but we didn’t make it to any of those, so perhaps that’s why we didn’t see more?

As someone majoring in Indigenous Studies, and because I wasn’t satisfied with what I learned, I’ll tell you what I know myself, and I hope, if you visit, you’ll track down something wonderful and send me information. I do intend to re-visit Tassie and track down more for myself.

I set off on our adventure keen to uncover how settlement may have affected Indigenous peoples in Tasmania, who before settlement knew the island as lutruwita (lu-tru-wee-tah). In 1803 settlers arrived to form Australia’s second British colony at Risdon Cove, and it was named Van Diemen’s Land as part of the New South Wales settlement. In 1856 the island was granted self-government and the name officially changed to Tasmania. Of course, I realised that just like every part of Australia, settlement was likely a destructive time for Indigenous populations, but how destructive? What happened? Did any clans survive on their own lands? What was the initial reaction from either side?

Unfortunately, the story isn’t a kind one.

Before settlement it is believed there were nine Indigenous Nations living on Tasmania, who traded with European sealers with very little animosity, but once settlement began, Indigenous peoples were pushed off their lands in order for settlers and convicts establish colonies and farmland. Land would be fenced off and distributed for farming and cropping, but when Indigenous peoples rely on their homelands for food and water, to fence this off means desperation and lack of ability to survive.

If you’d been living peacefully on lands for no less than 35,000 years and all of a sudden found your lands fenced off resulting in your family starving, what would you do? Of course you would need to fight, you would be driven to fight; fight for the right to eat, and stay alive.

Most people don’t understand that for the most part, Indigenous Australians were not historically a nomadic peoples, instead they existed in designated lands which they cared for and used to sustain all they needed, sometimes trading with neighbouring Nations for tools or foods they may not have access to on their own Country. So it was not as simple as being kicked off one area of land by settlers and moving on to somewhere else, Indigenous peoples could not just take over someone elses lands. Sadly this is the theme right across Australia, not just Tasmania, but on an Island state so small, losing lands would have had horrific consequences.

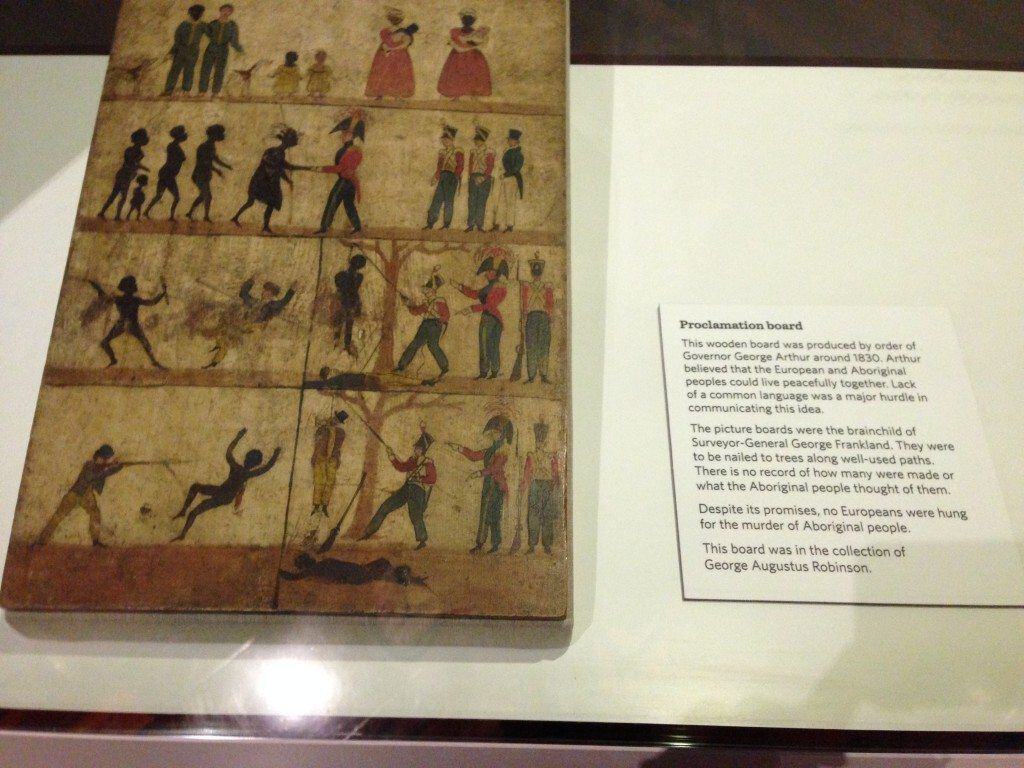

Lieutenant-Governor Arthur declared martial law in 1828 resulting in Aboriginal clans being forced out of areas and away from white settlers, murdered or incarcerated. Those who were not forced out were decimated by European diseases which killed many Indigenous peoples who had no immunity to such health issues.

Surviving Indigenous Tasmanian peoples were forced onto Bruny Island, Flinders Island, and other areas, where most died due to poor conditions and disease, before a settlement at Oyster Cove was formed and those who survived were mostly left to their own devices there.

There is, today a Tasmanian Indigenous population who have worked hard to revive and continue Indigenous language and connection to land and culture, so as proven right across Australia, our First Peoples are resilient and determined and this should be celebrated.

My Most Treasured Indigenous Insight While In Tasmania.

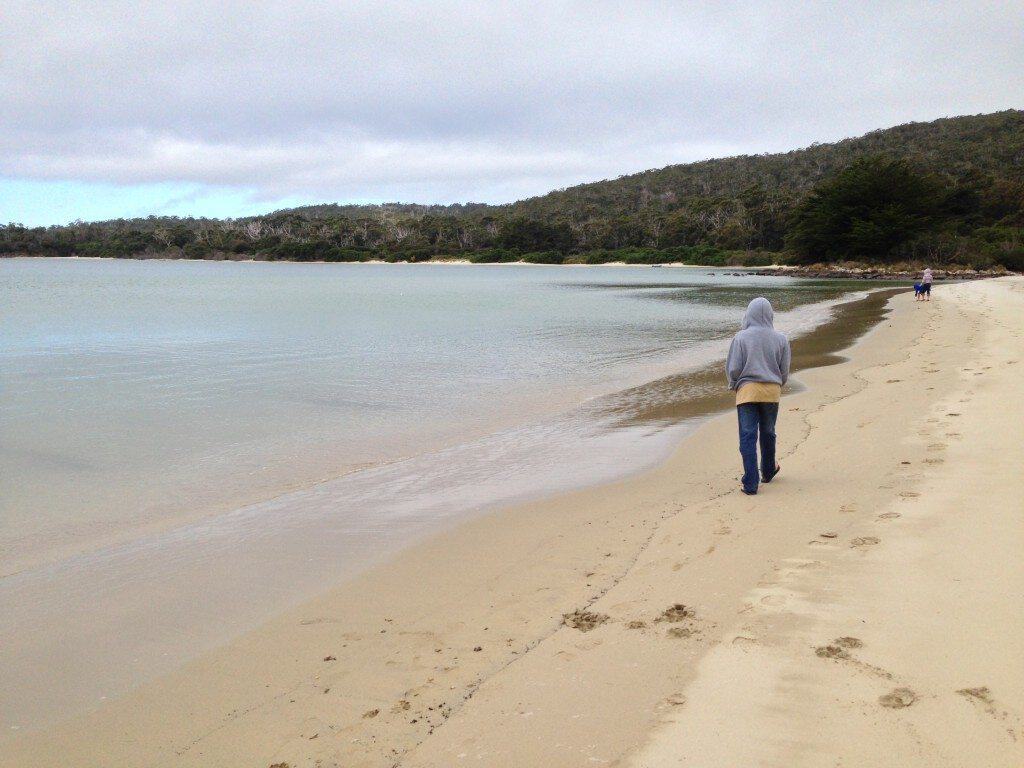

One area we did visit that holds Indigenous significance is Recherche Bay.

Many people would have heard of Truganini (1812-1876), a brave and amazing Aboriginal woman who survived the destruction and decimation of her peoples, caused by white settlement.

Truganini was born in Recherche Bay, daughter of the leader of the region. While much of Truganini’s family were brutally killed, Truganini travelled with her partner Woorraddy who accompanied George Robinson, serving as a guide and interpreter, during attempts to relocate Indigenous populations to several island settlements. During this time, Truganini became disollusioned with Robinson’s mission, realising that his attempt to remove and relocate Aboriginal peoples would all but remove the chance for traditional Indigenous life in Tasmania, and instead urged her peoples to stay and with them settled at Oyster Cove.

Truganini passed away in 1876, and is believed to have been the last surviving full-blood Tasmanian Aboriginal person. While fighting occured when her remains were recovered from the Hobart Female Factory site in 1878 after much protest and fighting, in 1976 her ashes were scattered on the D’Entrecasteaux Channel, fulfilling her wishes almost one hundred years after her death.

I, stood, one small person looking out the the D’Entrecasteaux Channel, and Recherche Bay, and with my standing, felt the gravity of settlement, the pain of a peoples who did not ask for us to be here, and the pain of one woman who fought for survival for herself and her peoples.

In all this sadness I felt a renewed hope that as a country we can move forward. We can never undo what has been done during the devastation caused by settlement, but we can be mindful and reflection and acknowledge that while we have grown into an amazing country, this has not been without loss and pain.

Together, as a united country we must not lose sight of the most important part of this country. The land. It has nurtured a culture now considered the oldest continuing living culture in the world, and we must care for the land so it continues to nurture the people who now call it home.